In the beginning there is the canvas. High, short, wide, long, small, large, very large. And on the canvas, a wash of white tempera, applied in a thick, undulating manner with a large round brush that prepares a candid, vibrating substrate. And then the colours, taken from a palette-table (as it is supported by a twisted olive trunk in the form of “legs”, like Ulysses’ bed): a palette sumptuously encrusted after forty years’ service, with constantly growing lumpy little mounds of paint. The highest ones are yellow and white, the solar signs of Luciano Pasquini’s paintings, imbued with light.

The colours are applied on the canvas starting from top to bottom, so that the shape is created via a progressive and guided descent of substantial brush strokes, without a drawing; that is, with just the drawing in the painter’s head, familiar ever since his emergence with a range of subjects he recognises himself in and via which he is recognised: floral compositions, summer landscapes, winter landscapes, densely populated villages, seascapes. The brushstrokes are what build, with skilful allusions to the structures and surfaces, the identity of the individual shapes. In the bunches of flowers – often carefully composed and arranged obliquely – the myriads of petals forming the cupolas of the hydrangeas become rounded and concave. They suggest the open, shadowless corollas of the poppies in blazing, frayed red. They evoke the spiky blue artichoke flowers like the bristles of a brush, with an effectiveness and rapidity that the complicated botanic description (read it to believe it) could never achieve. The daisies create vigorous radial patterns.

And in the landscapes, on top of a grainy texture that emerges from the leanest of strokes – the watermark of the vitality that perpetually moves the sea and shakes the earth – strokes of the brush and swipes of the spatula that build thicknesses and textures: the stratified plastering of the houses, the hard tiles of the red roofs, the regular furrows in the fields, the smooth expanses of snow, the slopes of the cliffs sliding down into the sea, the floral explosions of the yellow and purple hedgerows in the summer season. Where required, a slightly abrasive stroke over a background of already dried colour, using a process reminiscent of the ancient technique of “sgraffito” on the wall, allows the texture of the most minute underlying white reliefs to emerge. And then the sky takes on an irregular haze of water vapour pending densification, and the sea ripples with a subtlety of small, quivering yet innocuous waves.

I wrote years ago that to look at Pasquini’s paintings, “among the numerous aesthetic sensations, what prevails for me is the impression of hearing the sound of breathing. The hoarse telluric breath of his hilly landscapes. The deep blowing of the wind that moves the sea, pushing the waves over vast expanses. The hot, quiet breath of the houses squeezed together like a flock of sheep at night. The rustling sighs of the freshly cut flowers that carry with their jagged corollas the air of the bushes and meadows they come from. What’s missing however, is the breath of a living creature, be it man or beast, in a world made up of expectation or absence which does not seem to need a pulsing life on the surface and instead draws its special form of organic existence from latent sources of energy”.

Indeed, in these visions, carefully purified of any trace of humanity – except that which can be deduced from the presence of the homes built and lived in, the neatly cultivated fields – the protagonist is a benevolent daytime environment that never inflicts storms, where it never gets dark, where the snow that fell silently spreads protectively like thick icing over the valleys and highlands. Rarely does the lighting in these paintings come from a visible source, rather, it is usually soft and diffused, as though inside and mixed with the paint itself, so that at the time I defined it as “an inner light that gilds the hillsides, making the meadows filled with flowers in spring palpitate with purple reflections, opening the transparencies of a sea transfigured into dark crystal. And in the houses of the steep, pleasant villages, such as those found among the hills and dales of the countryside in central Italy, and especially in Tuscany, the light is not propagated by the windows – which look like notes or commas or louvers where sharp, dark shadows thicken – but instead it comes from the nuanced colours of the walls and the reddish roofs that emanate a brightness which is perhaps a reflection caught from the sun of an invisible sunset or maybe just an intimate, secret richness of their own”.

The recurrence of formal subjects and solutions in Pasquini’s prolific paintings transmits the image of an artist true to his own expressive line, the changes of which – in size, density, chromatic tones – can only be perceived in the long and very long-term: he is refractory to experimentation as an end in itself, too in love with “his” subjects to ever get tired of them, compensated by the imperceptibly yet constantly introduced variants that manage to make every painting look different from the others.

Pasquini’s loyalty to his own creative style has the long, slow rhythms of a rural, farming background, still today a topical element and constitutive value of his and his family’s life decisions, perched as they are on a hillock at Rignano sull’Arno in a landscape of astounding beauty, amidst well-tended olive groves, dark, towering cypress trees, patches of broom, undulating clumps of purple irises, with good olive oil, genuine wine, cherries saved from the voracious beaks of the blackbirds: seasonal commuters between the deep heart of the Florentine countryside and the Adriatic coastline beneath Mount Conero.

And in the midst of this continuation of life, something that has been of fundamental importance – as explained by Pasquini himself and also found in his biographies – is the albeit brief period he spent at the San Gersolè primary school, from first to third grade with teacher, Maria Maltoni. His admiration for the accurately delineated and patiently coloured naturalistic pencil drawings of the fifth- and sixth-grade students never abandoned Pasquini: rather, it worked secretly yet tenaciously inside him, until bursting out into an authentic adult talent as a painter, an exuberant and natural talent just like the flowers, radiating the energetic, vibrant colours that he started to portray, all linking up to the common denominator of that early botanical imprinting. You could call him an unconsciously trained, self-taught artist. Still standing out today on his cluttered table (nevertheless under his control thanks to his commendable habit of documenting and archiving everything) almost like an object of veneration, is a beautiful edition of “The diaries of San Gersolè” published in 1949 in Florence by Il Libro – and also from ten years earlier, the better-known “San Gersolè Notebooks” with a preface by Italo Calvino – where the word and the image have nature and country life as their protagonists, with their measured spaces and archaic rituals reaching the threshold of modernity.

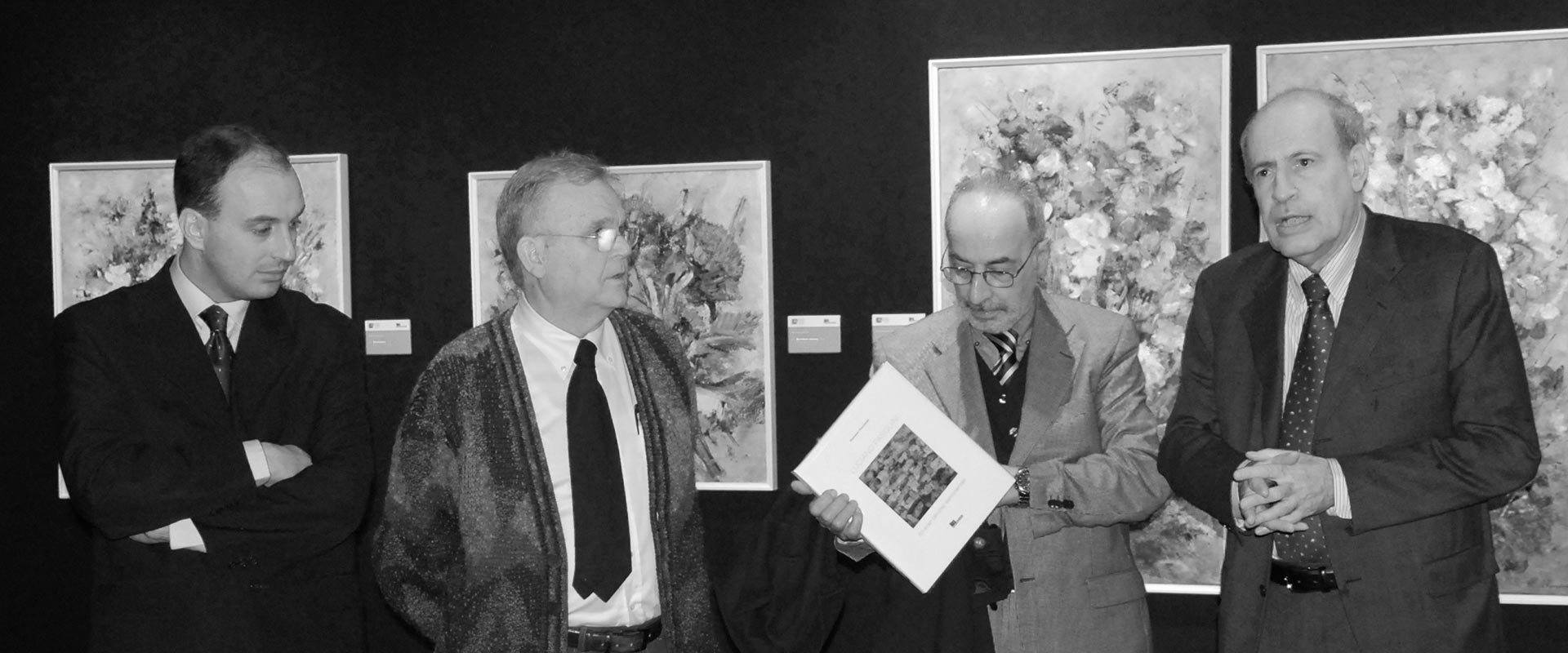

And Pasquini himself is one of those neat, plump children in the photo on the first and last parts of the cover of the catalogue of the exhibition “The Teacher and Life – Maria Maltoni and the School of San Gersolè”, that the Municipality of Impruneta organised at the Ospedale degli Innocenti of Florence in 2007.

It is this invisible yet unshakeable and earthy depth that gives Pasquini’s paintings their genuine long-term vocation in the pleasure and affection of those who, for any reason whatsoever, place them or find them under their gaze. Because if we were to dig in the invisible layers of the past and present of the artist we would discover the teacher, Maltoni, the older children with their beautiful drawings, the builders of the houses with the red sloping roofs, the labourers in the fields who have ploughed and sown, leaving regular tracks on the sun-blessed hillsides; there would be the olive trees and cypresses, the broom and the undertow, the flavours of the olive oil, the wine, the cherries in spring. This true, solid world, antique and modern at the same time, lies lurking in every one of Pasquini’s paintings, like a root system in the ground that we can’t see but which allows the tree to grow, and the soil itself, bridled and restrained, to resist without crumbling under the first rainfall. If we own a painting by Pasquini we own a fragment of Tuscany, a sliver of Italy: Italy at its best, in which man has known how to shape the beautiful nature of the places with his passionate and respectful work.

From the monograph “BUILDING WITH COLOUR” produced on occasion of the exhibition in the Certosa of Pontignano – (Siena).

May 2016 – October 2017.